Framing

This will surprise no one, but I have never been one to give much weight to personality tests and horoscopes. As a self-proclaimed “type A” person, I tend to draw heavily on reason, logic, organization, and a healthy dose of stubbornness to power through any task or conundrum in my life. I make lists, break things down into progressive steps, get granular with the details, and sometimes struggle to let go of control and delegate the workload. Even the EPS strengths test that I took all the way back in 2017 has me pegged as a super-fun “type A” person, with learner, responsibility, context, achiever, and discipline being my top five strengths. What I lack in “woo!” I more than make up for in logistical spreadsheets, classroom engagement tracking, direct communication, and colorful school supplies ?.

But in all seriousness, I am a logistics gal and I take pride in my executive functioning, organization, and communication skills. When I had my second child and life got chaotic, my ability to hold all the details and keep track of the logistics started to falter, and this was a big shock to my sense of self. My life (and home) got a little messier, and I struggled to maintain the organizational systems and practices that were cornerstones of my identity. I have since had to adjust my standards and let go of some of the time-consuming systems that I had previously been so diligent about maintaining. I once read a tweet from organizational psychologist Adam Grant that sorting your inbox into labels and folders is a massive waste of time. Grant states, “It takes an average of 67 hours a year [to sort your email into folders], and actually makes it harder for you to find stuff. It’s more efficient to just archive all your messages in a single folder for saved mail.” I am 100% guilty of the “zero inbox” with labeled folders and subfolders, so I can only imagine how many hours I have wasted dragging and dropping every last email out of fear that I will one day need to resurrect my digital archives on Admissions Open Houses. I want to be more efficient with the professional tasks that do not bring me joy so that I can preserve more time for the aspects of my job that I love – collaborating with colleagues, meeting with students, researching content, and designing curriculum.

As I reflect on my work ethic and style over these past fifteen years of teaching, I recognize that I value personal responsibility and integrity a great deal, and that clearly shows up in my professional practice. Early on in my career, I measured the quality and value of my work based on the hours that I put in. I am pretty sure that this stems from having parents with intense careers and work ethics, and from my New England, Protestant upbringing. While I still clock a lot of hours during and beyond the academic day, I have worked hard to become more efficient and to establish boundaries between my professional and personal time. I hold off on sending emails in the evenings or scheduling meetings during every free block that exists in my schedule. I let my inbox get a bit unwieldy from time to time, and I don’t even color-code my desktop folders anymore! While this has been somewhat liberating, it has also challenged me to release my grip on perfectionism and to have empathy for myself and my colleagues. I spent the first decade of my career honing my executive functioning skills so that my colleagues and supervisors would respect me for my professionalism and work ethic. This is a hard truth to admit, but one that I think many young teachers, and probably many young female-identifying teachers, can relate to. I still care a great deal about being organized, reliable, and professional in the workplace, but I now am willing to forgive myself when things inevitably slip through the cracks.

Professionalism | Executive Functioning

| Indicator | Comments & Evidence |

| Approaches recommendations for improvement receptively and responsively | My defense tendency is to be brutally candid and sometimes self-deprecating in my own evaluation of my performance and skills as a way to lower expectations and let others know that I am aware of how I could improve. I don’t love this about myself, but it speaks to the fact that I am not 100% comfortable receiving critical feedback. I really want to grow in this area, as I value feedback and see it as critical to personal and professional development. Another moment of vulnerability here – praise and validation are important to me as a teacher. Admitting this makes me uncomfortable, but I am trying to lean into this opportunity to honestly reflect, and that means tackling my ego in this experience, too. In my first few years of teaching, I received a lot of positive praise for my work ethic, professionalism, and content delivery in the classroom. I was young, making well below minimum wage, and working my tail off, so this praise and recognition meant the world to me. It also established what I can now recognize as an unhealthy dependency and cycle of hard work and praise in my professional career. The praise validated the exhaustive input, which in turn pushed me to just work harder, which in turn made me more burnt out and reliant on positive feedback. When I came to EPS, the praise came to an abrupt halt and I was left wondering if my style of teaching was good enough for an EPS classroom. I stubbornly put my head down and just worked harder in my lesson preps, but the mentorship and praise that I was craving never materialized. Not only did I have the worst case of imposter syndrome that first year in the Annex, but I questioned if teaching was the right career for me. Bart told me that the Pacific Northwest wasn’t a very emotive place and that our students just took a while to trust and warm up to new adults, and I remember asking him if this was the case for the adult community, too. He laughed and told me that I was doing a great job, but I struggled to accept the compliment. Seven years later and I still look for validation and recognition for my hard work and contributions at EPS. I think that will always be an aspect of my professional practice that I navigate, but I have also found new sources of confidence and leadership experiences that help fill my personal need for reassurance. |

| Displays openness and comfort with visitors observing class | Despite my feedback fears, I actually enjoy having visitors, colleagues, and observers in my classroom. I love sharing my craft, inviting others into the unique community that I have built with my students, and sharing in the experience of studying history. I look forward to John’s observation days and the follow-up conversations that we have, but that is probably because I overly prepare for these lessons and try to get out in front of any critical feedback by naming what I wish I had done differently before he has a chance to state these weaknesses. What I am always reminded of in these conversations is how thoughtful and caring my colleagues are in their delivery of feedback, so the scary critique that I am trying to avoid never is the reality. There have been a few instances when John has asked if a new-to-EPS teacher could observe one of my lessons to get a sense of my classroom management practices. This always surprises me because I have no formal training in this area, but I must give off the impression that I run a tight ship because this request has come my way more than once. Whenever someone new is in the room, I always want to follow up with them to hear their impressions of how the class went. Another set of eyes helps me better understand the patterns of participation in the room, the moments of distraction, what students are actually doing on their screens, and how my lessons land with the kids. I also love it when my students get to see adults being vulnerable in their practice and collaborating with colleagues. Sometimes the debrief with my students is just as rewarding as the debrief with my colleague after an observation. |

| Seeks out diverse opinions of others for guidance | This is one of the greatest gifts of collaborative teaching. Whether it is brainstorming a new unit, planning the logistics of a field trip, or group grading a student essay, I always find that my own understanding deepens when my colleagues share and contribute. If I am stuck on a problem, I will often swing by Wen Yu’s office to think through a solution. If a student interaction did not sit well with me, I’ll reach out to Verity or Bess to debrief the experience. When I feel like I have exhausted all of my options with a student, I’ll go find Monica and ask for help. And when I know that I lack the experience or knowledge to make an educated decision on my own, I will connect with trusted colleagues like Jamie, Karen, and Anne for guidance. The nature of collaborative teaching means that I am rarely making decisions or designing lessons alone, and this is one of my favorite parts of working at EPS. |

| Manages and prioritizes professional tasks and responsibilities | To a fault, yes. See the “framing section” for more details on this indicator. |

| Communicates and responds to students, parents, and colleagues in a timely and constructive manner | Yes, although the more chaotic my life becomes, the more I am aware of my tendency to avoid or delay prompt responses to emails. I often teach two sections back-to-back, and will open up my Inbox after three hours of teaching to find upwards of 30 emails that need filtering and responses. This immediately turns on my avoidance tendencies, which only makes the problem worse. This is something that I would like to work on because I know that a quick pause often turns into a long delay and I end up apologizing for my tardy response, and it never feels good to start an email with “Sorry for the last response…” I wish the email correspondence could be a smaller, more manageable part of my day, AND I also want to improve in my ability to respond in a timely manner so that I don’t drag it out. |

Assessment Practice

| Indicator | Comments & Evidence |

| Designs major assessments that reflect course outcomes and posts them at the start of each trimester | This is an indicator that I can proudly say I check every trimester. I always map out my courses in a GoogleDoc in advance (see example of US History planning document here) and schedule units, QAs, and MAs before hitting publish on my Canvas pages. There isn’t always a lot of detail or a formal assignment sheet attached to each assessment on Day 1, but the assessment title and date is always up from the start of the trimester. Typically I will populate the details with 2 – 3 weeks notice for students so that they can anticipate the actual workload. |

| Designs assignments to be graded and returned in a feedback cycle of seven calendar days | Grading is hands down the most inefficient part of my practice. I am a slow reader with high reading comprehension, so it has always taken me longer to get through a student essay and provide narrative comments. I also take pride in the quality of feedback that I give to students, especially on writing, and this inevitably slows me down. I am well aware of the many studies that identify the sweet spot between the effectiveness of feedback and the turnaround time of that feedback. Intellectually I get that students need to receive timely feedback while the learning experience is still fresh in their minds. And…I rarely meet the 7-day turnaround rule at EPS. It’s not that I don’t want to meet this rule, it’s just almost impossible given my limited prep time in the evenings and on weekends, the nature of teaching trimester-long courses, and the fact that most of my grading is analytical writing. I am always envious of my officemates as they fly through Calculus exams on the same day that they administered the final. I can’t help but compare my grading experience to that of other teachers and feel jealous of the hours of living that they get to do while I am staring at a computer inputting comments on Canvas. Bart once told me that it is never a good idea to compare your teaching experience to that of another teacher, but boy is it difficult to avoid comparison when it comes to grading and meeting the 7-day rule. I would love to be more efficient and productive with my grading as long as the quality and impact of my feedback does not plummet. I hope that my students recognize the thought and time that went into my comments, even if they come back 12 days after submission. This might be a “me” issue around perfectionism that I need to address, but I struggle to lower my standards to meet an unrealistic deadline. The problem is that once you blow by that deadline, it is hard to hold yourself to a secondary deadline of your own making. Without completely opening a can of worms here, I know that my grading inefficiencies are a major driver in my grade inflation. I am more inclined to be honest and direct with grades when I have the time to give substantive feedback that justifies the point deductions. When I am strapped for time, my cursory read-through of an assignment often leads to higher grades with fewer comments. Ideas for streamlining some of my grading in a way that still feels genuine and in line with my teaching values include: 1. Rely more heavily on pre-populated rubric comments, 2. Incorporate more in-class / in-person grading and feedback with students 3. Assign fewer graded pieces in a trimester course 4. Grant myself permission to give the grade without justifying every point 5. Set timers and schedule grading slots on my weekly calendar 6. Chip away at the grading stack rather than sit down for marathons before deadlines. |

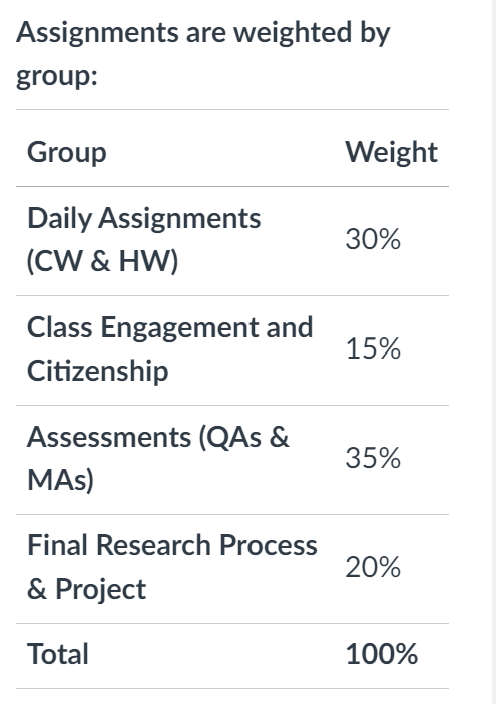

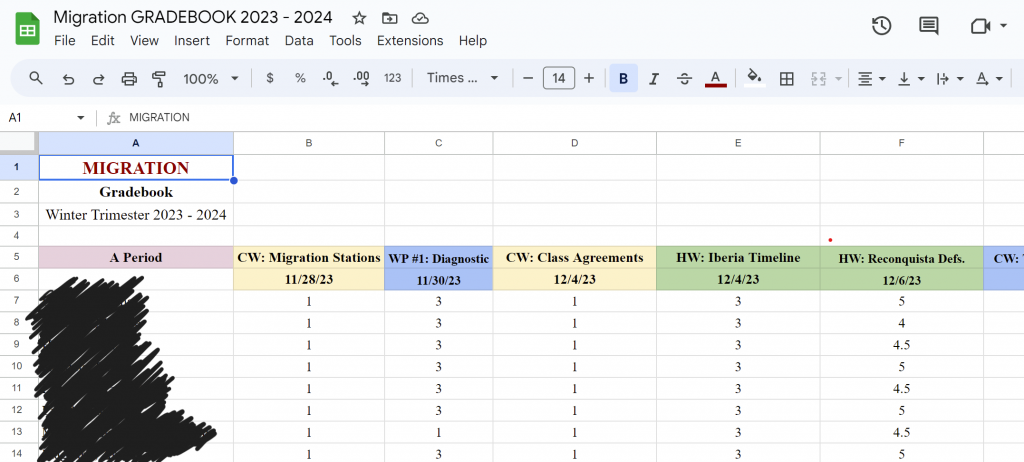

| Ensures the number of assignments in each course is neither excessive nor deficient – providing appropriate time for quality student performance and meaningful teacher feedback | My approach to gradebooks has shifted a handful of times in my teaching career. I used to go with the “total point accumulation” method, where every type of assignment had a standard number of points associated with it, and the student grade at the end of the trimester was simply points earned divided by total points assigned. The challenge with this method is that you have to know what you are assigning for the entire trimester before you start the course, otherwise you could end up with homework assignments counting for 70% of the course grade without fully knowing it until the last few weeks. The second method, and the one that I have stuck with at EPS, is the weighted categories approach. I typically count daily coursework (HWs & CWs) at 35 – 40%, class engagement and citizenship at 15 – 20%, and assessments (QAs and MAs) at 40% of the course grade. This tends to be a more balanced and predictable approach to grading, and yet it still requires a lot of planning and projections for how many assignments will exist in each category. Students are quick to point out when a single homework assignment or reading quiz is overly represented in the final grade, even when I meticulously tried to avoid that from happening all trimester. In those scenarios, I hear the student’s reasoning, I check my math a few times, and then if the representation of particular assignments in the final grade really doesn’t feel fair to me, I will own that mistake and communicate an adjustment to the class. |

Evidence

This is an odd section to gather and present evidence for, since no one wants to see a screenshot of my inbox. Here are a few examples that illustrate my thoughts and practices for the indicators above:

My Internal Planning and Gradebook Documents: