Framing

When I first began teaching, I was very much in student mode. I overly researched each topic, I took detailed prep notes, and I packed way too much into a 75-minute lesson. I stayed one step ahead of my students and did my best to make up for my lack of experience by overly preparing for each class. My default method for delivering all of this research in a structured lesson was a visually engaging and often text-heavy Power Point slide deck. Having the slides by my side allowed me to present detailed information without having to memorize it all for each class. The slides were my content security blanket as I tried to build confidence in my content knowledge and expertise. After countless lectures that probably put most of my students to sleep, I realized that I was crafting lessons to suit my learning and teaching needs. I was teaching to the type of student that I once was, not to the students who were in front of me.

Differentiated teaching continues to be an evolving area of learning and growth in my practice. The one-size-fits-all method of classroom teaching clearly (and thankfully) has evolved, and today there are endless pedagogical approaches, teaching strategies, research studies, and accommodations to support the diversity of learners in the classroom. I’ve experimented with a lot of these strategies in the humanities classroom, and what I have found is that it is important to find teaching strategies that blend with my educational philosophy and teaching values. One can easily get overwhelmed and lost in the many teaching tools available for differentiated instruction, sacrificing their sense of self as a teacher for the need to try it all. And yet it is so important for a teacher to keep trying, to keep learning, and to keep responding to the students in their classroom. I have observed that students learn best when they are seen and supported for all aspects of their identity, and the same goes for teachers. When a teacher has the trust of the school and the students to be their full professional selves in the classroom, that is when genuine learning relationships are built, and the real needs of a student can be identified and met.

Interestingly, some of my most valuable hands-on experience with differentiated instruction came from my time coaching sports in the boarding school world. When I was a student athlete, I always appreciated the ways in which my coaches supported the unique development of each player on the field. From the pacing and chunking of a two-hour practice to the individualized feedback that made its way into our drills, my coaches were always thinking about the overall growth of the team while also supporting the development and needs of each player. This realization came to me while I was sitting in a faculty meeting at St. Mark’s about moving to a block schedule for the next academic year. Teachers expressed their hesitations about being able to keep kids engaged in a lesson for almost double the amount of instruction time. Veteran teachers knew how to craft a focused 45-minute lesson, but the idea of keeping teenagers excited about learning Latin or Physics for 85 minutes seemed daunting. Just then, our varsity soccer coach spoke up and encouraged us to think in “chunks” when crafting lesson plans. She said that if she planned an entire practice around one scrimmage, her players would probably injure themselves and tap out by halftime. She walked us through her warmups, the focused agility and skill drills, the smaller 3v3 group work, the full squad scrimmage, and then the cool down. Suddenly, a group of anxious teachers was able to see an intentional narrative and progression emerge in this example of a soccer practice. There was a beginning, middle, and end to the player experience. There was individual development, small group work, and full team practice. Planned instruction framed each phase of the practice, while organic, individualized coaching worked its way into each activity.

Every time I sit down to create a lesson (or unit) from scratch, I am reminded of the valuable parallels between coaching and teaching. This helps me break down the curriculum design process into chunks without getting overwhelmed by the full experience. I am sure that teaching programs have a much more sophisticated term for this style of curriculum design than “chunking and layering,” but having never formally studied education and teaching in my own academic career, I tend to draw from my personal experience as a student, an athlete, and a coach in my approach to curricular design.

Classroom Culture

| Indicator | Comments & Evidence |

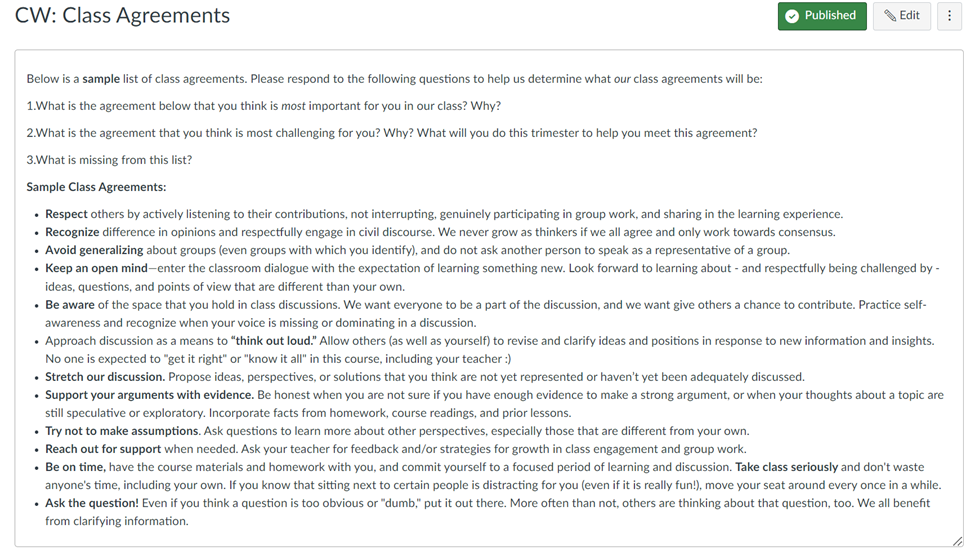

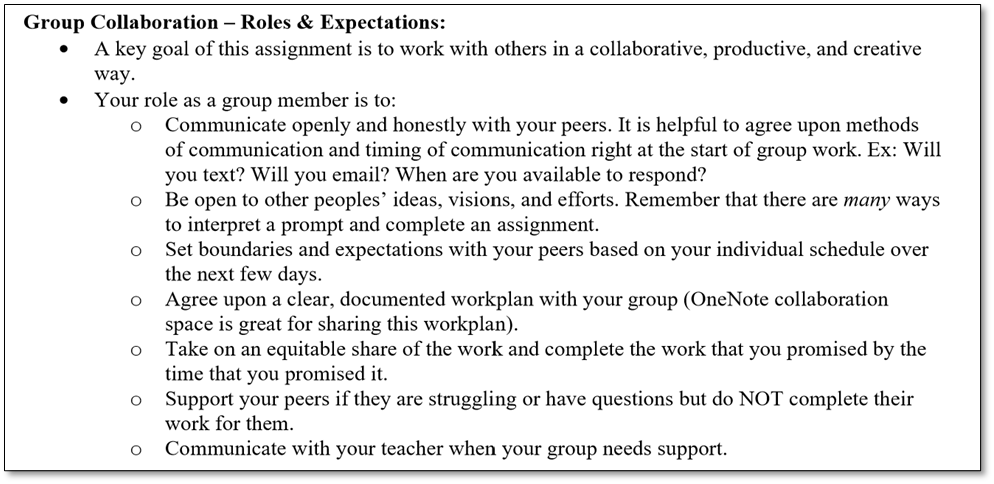

| Coaches and reinforces peer-to-peer dynamics that are appropriate and constructive | Partner / group work is present in almost every class that I teach. Sometimes this looks like a quick pair and share opening question or jigsaw table work. Studying history is all about participating in a shared, discussion-based learning experience, and group work is one way to break those larger discussion moments down while still providing an opportunity for students to process and engage with material through discussion. I also find group work to be an excellent time for me to observe how students are connecting with the material because it challenges them to step into the leader / facilitator role in an activity and walk each other through the content in their own way. While group work is wonderful for all the reasons listed above, it can also be quite difficult, especially at the start of a course when everyone is just getting to know each other. I find that providing norms and expectations for group work early on is helpful. See the evidence section below for an example of group collaboration expectations. The difference between group work for 9th graders vs. 11th graders is also significant. The 9th graders are still developing their own work styles, which makes it difficult to communicate the quality and expectations that they have for themselves, let alone for another member of their group. Additionally, 9th graders tend to turn to the teacher before communicating directly with their peers when things start to fall apart. Their instinct is to share their frustrations with an adult and then hope that the adult will manage the uncomfortable group dynamics for them. This makes sense for where 9th graders tend to be socially, but it also demonstrates just how much intentional coaching and time is needed to support 9th graders in group work. Some strategies that I lean on when a student is complaining about other group members not pulling their weight are: 1. Keep communication at the group level as much as possible so that everyone is aware of the dynamics, 2. Encourage students to consider the perspectives of each group member before jumping to conclusions, 3. Hit reset and find the next productive step forward, and 4. Reflect on their own role in the group (during and after the project). For 11th graders, group work tends to be less about the personalities and social dynamics and more about managing the academic pressure that they feel junior year. Many juniors put so much weight on each individual assignment that they impose unrealistic expectations on themselves and their peers when it comes to group projects. This year in U.S. History, I witnessed one student openly chastise another for promising that he was going to get his portion of the PowerPoint completed the night before and failing to do so. The work clearly was not done, and that had an impact on their presentation the next day, but it did not warrant a very public reprimand. In that moment, the only option I had was to pause class, sit with both students in the hall, and ask them to take a few deep breaths. One student was embarrassed and defensive about his failure to contribute, and the other was so worried that she might get an A- on the project that she could not regulate her own emotions. Stepping out of the classroom helped tamp down the intensity, and so did a moment of silence to breath and collect our thoughts. I asked the students to share their perspective with each other (not to me), and then to figure out a realistic step forward given that the presentation had to happen that day. I assured the students that one missing part would not result in a failing grade, and I reiterated the need to communicate with each other directly. There are many other strategies that I could have employed in that moment, but the need to diffuse the situation and open up dialogue were my immediate priorities. Looking back, I probably would have encouraged some repair work (in the moment or after the fact) to accompany their group reflections. |

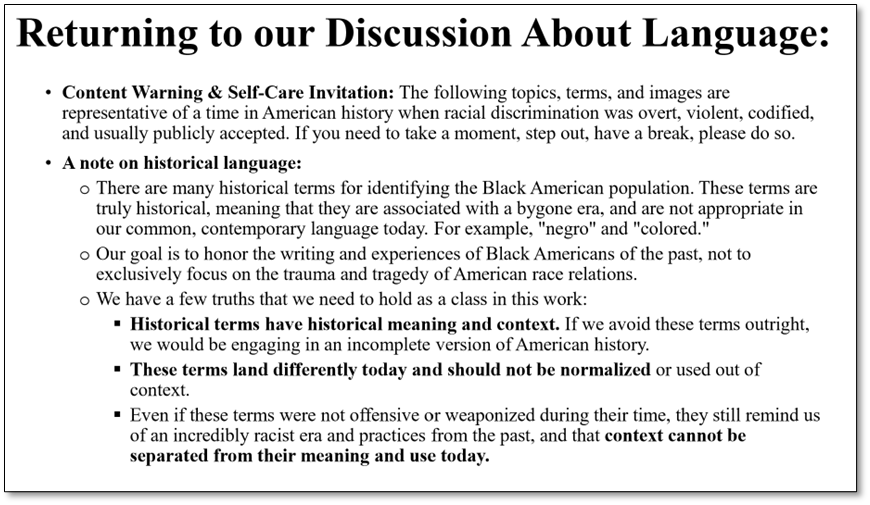

| Communicates behavioral expectations that are appropriate to class activities | This indicator is a huge part of teaching in the humanities. So many of our conversations delve into challenging and personal topics, so we spend a lot of time in class establishing boundaries and norms for our discussions. I always look to partner with the students in creating these class norms, since they are the ones directly participating in the learning experience, but I also have a short-list of “must haves” that I add at the end if they have not organically surfaced in our norming session. Recently, I am finding myself spending a lot of time defining terms and discussing the impact of language when studying history. This came up in our Black History unit when a historical term was referenced in primary sources. The term was not offensively used at the time, but is a product of an era that was incredibly racist and dehumanizing towards Black people. Even if the term was not weaponized during the 1950s and 1960s, its meaning is steeped in historical context and is no longer considered common or respectful language today. This was a topic of discussion in American Literature a few weeks before it came up in our class, so we had the benefit of building off of a discussion that our 11th graders had already started to engage in. I remember naming the nuance and complexity of this term in our course, and feeling grateful that we could all recognize multiple truths in this term’s use and prioritize caring for our peers in our discussion. Some of the framing and norms provided for this term are provided below in the evidence section. Additionally, Bess, Ed, Dr. Heather Clark and Jenn Oakes were incredibly helpful in discussing and framing these lessons. |

| Develops a mutually respectful relationship with each student, instilling confidence that the teacher is invested in their success | Individual writing conferences with 9th graders Making it a goal to meet with each student individually in the fall trimester Partnering with Learning Support Providing structure and clarity on assignments Intentionally arriving early (and staying late) to class to foster informal conversations and check-ins with students. Going to school events outside the classroom, such as games, performances, and art shows. |

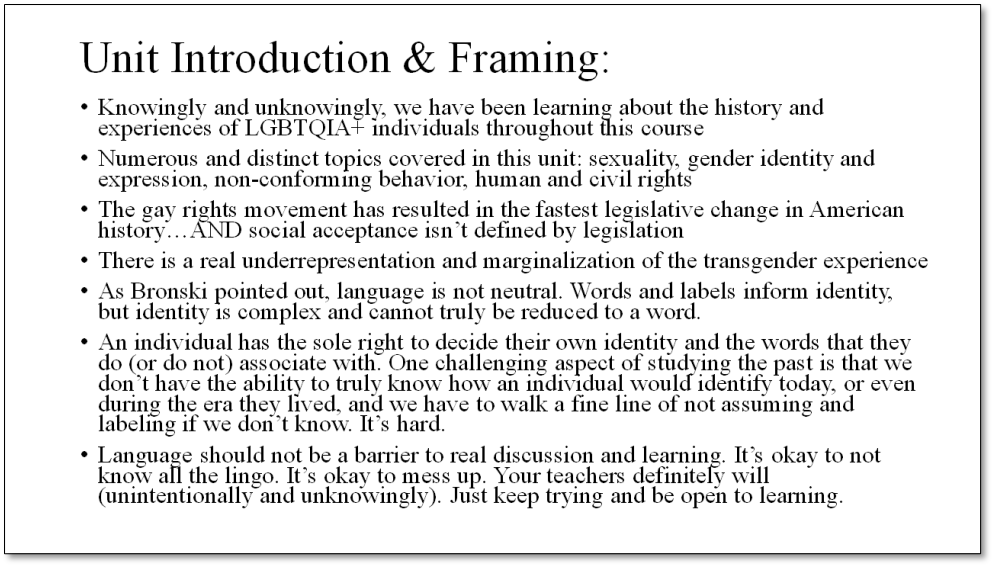

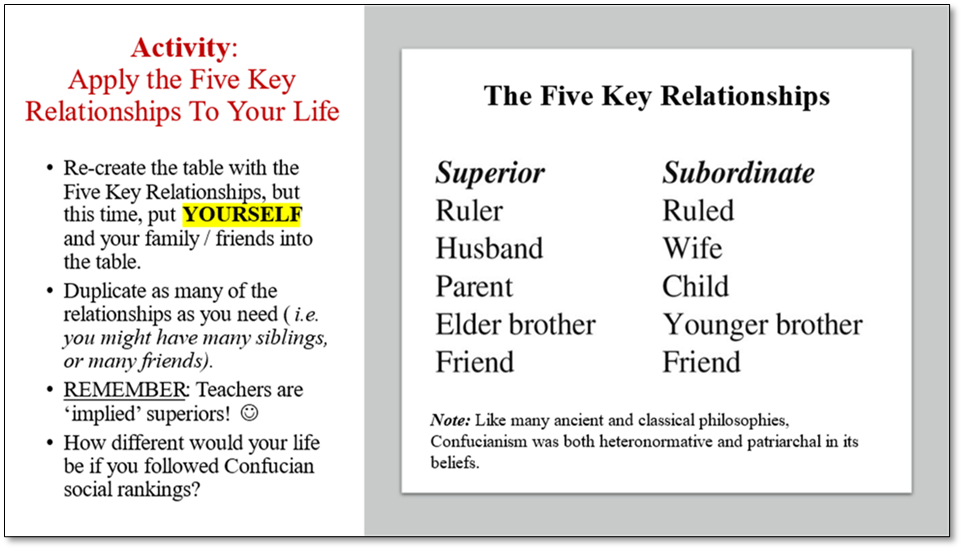

| Demonstrates cultural competence by promoting inclusivity | Selecting primary sources and course texts whose authors can speak from the “I” perspective Considering the identities and interests of the students in the classroom when developing curriculum. Ex: The LGBTQIA+ History unit and the 9/10 course redesign to include more global offerings such as South Asian history and Modern East Asian history. Language around learning accommodations Incorporating current events into lessons so that students are connecting with updated, relevant, and credible sources. |

| Designs and facilitates a classroom culture that promotes student preparedness, engagement, self-advocacy, perseverance, and collaboration | Provide unit overviews and daily agendas for students on One Note. Create varied opportunities for engagement with the material and participation in a shared learning experience – individual reflection, partner and small-group work, full class discussions. Design scaffolded moments of independence and self-advocacy for 9th graders and 11th graders. Ex: Writing conferences and research check-ins. I would like to experiment more with side-by-side feedback and grading with students. I learned about this in Dr. Catlin Tucker’s The Shift to Student-Led and am curious to hear how my colleagues (Alicia Hale & Sara Aguiar) |

Pedagogical Effectiveness

| Indicator | Comments & Evidence |

| Begins class sessions with a clear statement about the lesson’s objectives and place in the progression of the course | While I take attendance, students are prompted to “head on over into OneNote, pull up the materials and PPT for class today, take a moment to get class notes set up” Open the same way each class (introduction / framing of topic, agenda with homework, starter activity). Clear structure and routine to each class. Students know what to expect and where to find the materials. This makes missing class quite easy for students. All materials are organized and posted on OneNote. My “lecture notes” for students with this accommodation are my PPTs. |

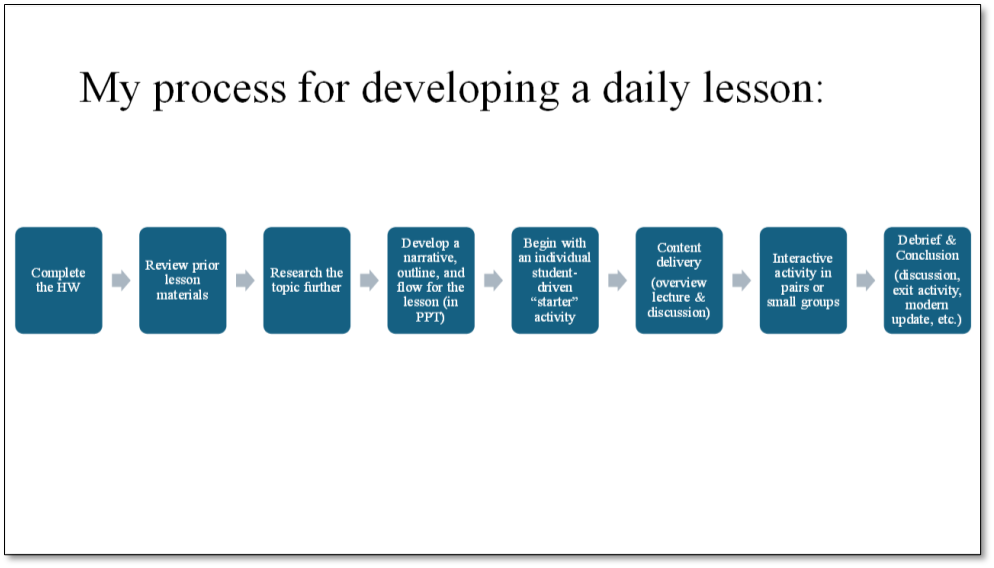

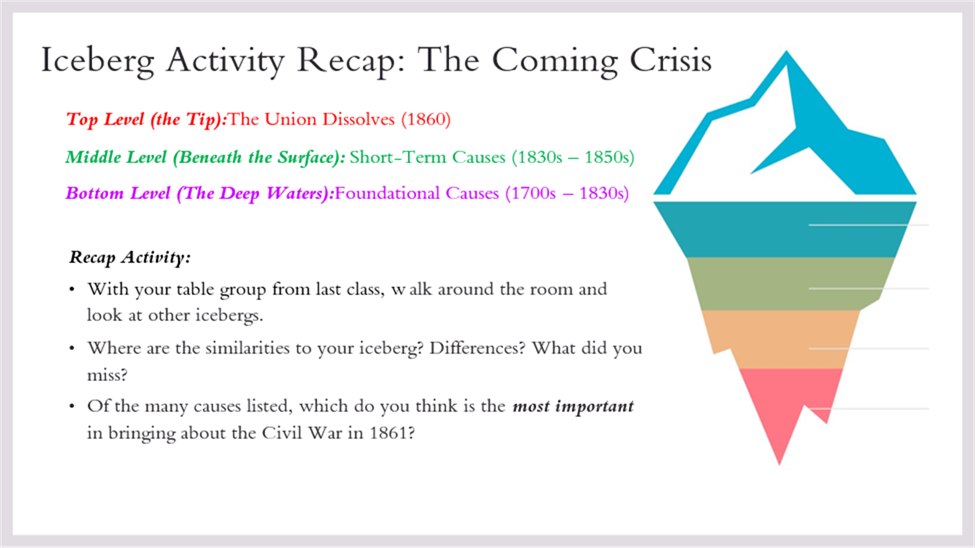

| Designs and implements varied activities in each class period | My default is Socratic lecture & seminar. Sometimes I call this style “interactive lecture and discussion” but I am not really sure exactly how to label it. It is not a passive experience for the kids, but it is not hands-on, experiential, activity-driven learning all the time. My brain tends to organize and prepare for a lesson by: 1. Completing the assigned homework (again, always). 2. Reviewing prior lesson materials. 3. Researching the topic further. 4. Crafting a narrative and flow for the topic. 5. Beginning with an individual student-driven “starter” activity (journaling, daily question, think-pair-share, image analysis, music…) – Dan Yezbick’s journaling EVO was super helpful in expanding my starters toolbox. 6. Some content delivery (for 9th graders, this includes reviewing and cementing the homework assignment; for 11th graders, this often means complementing and enhancing the homework assignment). This usually looks like framing or overview lecture and discussion before heading into an activity. 7. Some interactive activity in pairs or small groups (gallery walk, iceberg organizer, primary source analysis, simulations, etc.) Return to an all-class debrief discussion tying the information together & concluding the historical narrative. 8. If there’s time and the content lends itself to it, I will use an exit ticket or activity so that students have an individual moment of reflection and synthesis at the end of the lesson. |

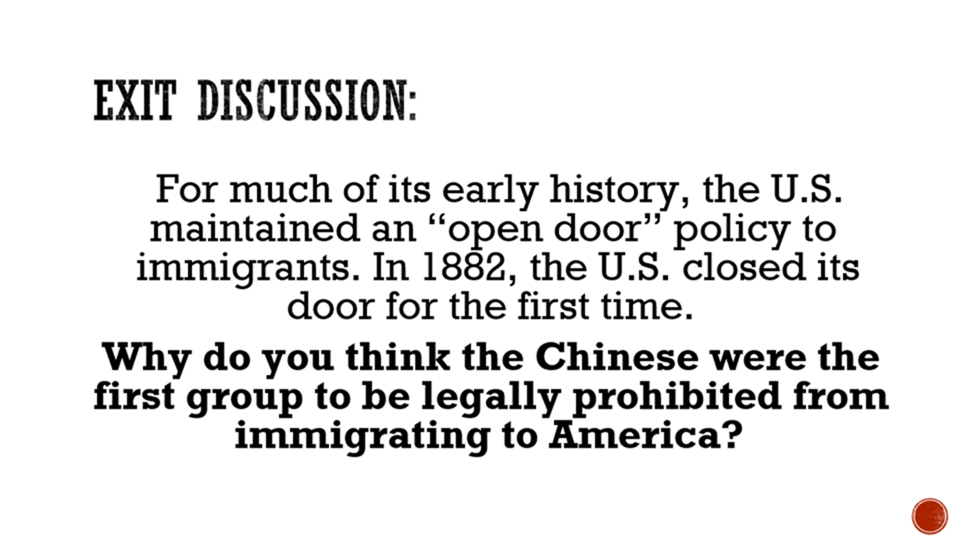

| Brings each activity to closure effectively and transitions intentionally to subsequent activities | For individual activities in which we have enough time to complete in class, I will almost always conclude with a wrap-up / debrief discussion for the entire class. I will ask for takeaways, reactions, questions, etc. I will also pose a few debrief discussion questions on a slide for the class to consider. I am the QUEEN of overplanning and not getting through it all in one class. This is not always my fault. I love it when students ask a question that takes us down a different path, or we get side-tracked by a current event that no one expected the night before when preparing for class. Part of studying history is engaging in civil discussion about the world around us, so I tend to lean into these spontaneous moments of student curiosity and inquiry when they pop up. That being said, I CAN do a better job of time management, realistic lesson planning, and getting back on track. These are definitely goals of mine. Sometimes I set timers for myself, appoint student time keepers to hold me to my schedule, or put time stamps at the top of slides so I am reminded of how long I have for each topic. One area that I have noticed some personal growth (especially since having my own kids) is flexibility with my schedule. I am not as rigid with the schedule, am willing to pivot when needed, can better recognize when I need to throw in the towel and move on, and don’t fret as much about the “review and repair” at the start of each class. All of this is to say that I often struggle to make it to my last slide, so the conclusion / wrap-up comments and exit ticket get sacrificed often. I would like to do more thinking (and research) on how this impacts my students. Do they feel that the historical narrative is incomplete or fraying most days? Do they need closure every day? Should I set a timer for this and cut off an earlier activity to preserve this cognitive moment for students? How many ways are there to conclude a lesson, and what functions as an effective conclusion for students? I almost always have a concluding point, discussion, or exit ticket planned, I just rarely get to it. I do often use a relevant current event / updating the topic in 2024 as a way to conclude the narrative and bring it back to the students’ lives. For example, we talk about Black Americans in the military during the Civil War and then look at data around Black Americans in the military today. Jamie gave a great presentation on setting agendas and using exit tickets during EPSRemote, and I need to circle back to her on the above questions. |

| Ensures that students are using technology and tools effectively | I try to provide explicit instructions and expectations around classroom technology. I prompt students to close tabs, to pull up daily course materials, and to create class notes for the day. I find that a starter (like a journal prompt or daily question) forces them out of their other tabs and into a productive technological space for taking class notes. I don’t do a great job of monitoring screens (partially because of the classroom that I am in this year but also because I am so focused on the discussion that I don’t always pick up on tech use). I use written feedback on class engagement and student comments to draw students’ attention to their technology use. I will sometimes go stand near students who seem to be doing other things on their computer until they switch screens. I let the whole class know when they should be taking notes and when it is clear they are doing something because what I am saying is not note-worthy. Online chess is the worst. |

| Concludes class with a summary and clear tie-in to the next class | See above response to “Brings each activity to closure effectively and transitions intentionally to subsequent activities.” |

Differentiated Instruction & Assessment

| Indicator | Comments & Evidence |

| Considers and addresses each student’s learning profile | Establish routine & structure for each lesson so that students know what to expect, have a familiarity and fluency with lesson structure, can easily follow along in class and at home (if absent). Ex: Daily Agendas, Power Points, consistent directions on homework assignments (ex: “actively read and annotate…”) Initial student survey inquiring about learning style, needs, and accommodations Basics: Pre-load student accommodations into Canvas, always include the accommodations link for assessments Daily journaling (thanks to Yezbick!) — ungraded, unstructured, focused “starters” Intentionally try to craft a narrative with an “opening” and “closing” for students |

| Designs class activities and assignments that engage and accommodate for both individual students and a diverse group of learners | Provide choice, when possible, on assessments. This includes choice on the format and/or question. Ex: Choice on short-answer & essay questions; emphasize skills and process over one definition of a “product”; 9th Grade History Research Project has three final options (research paper, symposium-style presentation, or podcast) Adjust pacing based on student experience and feedback (ex: stretching out the 9th grade research project from one trimester to two trimesters) Assessment “calendar” for 11th graders in US History (2023 – 2024): 1. MA: Forming A Nation In-Class Essay (open-notes, questions in advance) 2. MA: Forming A Nation Content Assessment (Multiple Choice, True/False, Short Answer with choice) 3. QA: Constitutional Convention Simulation (group discussion & individual written analysis) 4. QA: Trial of Andrew Jackson (group discussion & individual written analysis) 5. MA: Civil War Biography Spotlight (Partner Infographic, Presentation, & Individual Written Analysis) 6. QA: Storyboard Timeline for Module III (America’s Coming of Age, 1877 – 1950) 7. MA: Immigration Podcast (individual) 8. MA: Women’s History Museum Project (group project & presentation) 9. MA: Social Movements In-class Essay (open-notes, questions in advance) 10. MA: Final History Research Project (similar to 9th grade project, individual research with choice in final product) |

| Builds in opportunities for each student to contribute during each class period | Design lessons with “layers” of class engagement. This means that there is always an individual component (journal, daily question, starter, study hall), a small-group component (think-pair-share, table activity or discussion, team work for simulations / debates), and a larger class component (Socratic discussion, share-out of smaller group work, board work). |

| Provides alternative explanations of course concepts | Oral explanation and written (detailed class / lecture notes provided in PPT) Alternate resources and readings mentioned in class and posted on OneNote (ex: Khan Academy, Crash Course videos, alternate textbooks, podcasts, non-fiction books, movies) |

| Adapts instruction based on formative assessment | Respond to (perceived) difficulty of reading quizzes when writing next reading quiz Consider diversity of assignments and grades still remaining if a student struggled on an assessment Solicit student feedback (via reflection, via course surveys, via casual check-in discussions) Openly share feedback on the assessment, my experience grading, and my reflections (ex: when you earn an 83% on an assessment, does that mean that 17% of the course content and skills are not there yet and we just accept that and move forward? Invite students into the assessment process). Sal Khan approach — don’t give up on the 17%. |

Evidence

ESTABLISHING CLASS NORMS:

LANGUAGE & TERMS:

SYLLABUS POLICIES:

| EQUITY, INCLUSION, AND COMPASSIONATE LEADERSHIP (EICL) STATEMENT |

| The teachers of this course commit themselves to standing for the principles of equality, equity, inclusion, representation, diversity, empathy, respect, and empowerment. Following the leadership of the students and staff spearheading the Equity, Inclusion, and Compassionate Leadership (EICL) work at Eastside Preparatory School, we seek to foster the growth and development of active, informed, and passionate global citizens. As historians and social scientists, we acknowledge the role that academia has played in crafting and promoting a dominant narrative, reinforced by existing power structures, that has excluded marginalized voices. In the United States of America, this would include the voices of women, BIPOC, LGBTQ+, religious minorities, those from a lower socioeconomic background, and many other groups. The teachers and students of this course work to actively understand, critique, challenge, and expand on dominant narratives. We will identify existing biases within the discipline and seek to engage with perspectives and voices that have traditionally been underrepresented in curriculum. Our goals as educators are for our students to: 1. Practice accepting differences and seeing value in multiple perspectives. 2. Respectfully engage with opposing viewpoints in a manner that seeks to understand and find common ground with others. 3. Advocate for those who are not as empowered or privileged. 4. Engage as an active member of the EPS community and broader world. For further information about our EICL values and work here at Eastside Prep, please see the following resources: EPS Student Affinity Groups: https://www.eastsideprep.org/2019-20-eastside-prep-trustee-guide/equity-and-inclusivity/395336-2/ EPS Student Allies for Equity Club Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/eps.allies4equity/ EPS EICL Page: https://www.eastsideprep.org/student-life/equity-and-inclusion/ The EPS Anti-Racist Resource List: https://eastsideprep.org/PDF/2020-21/EPS-Anti-Racist-Resource-List.pdf |

Excerpt from my course syllabi on Class Engagement for students who identify as introverted or quiet in discussions:

Examples of Student Choice:

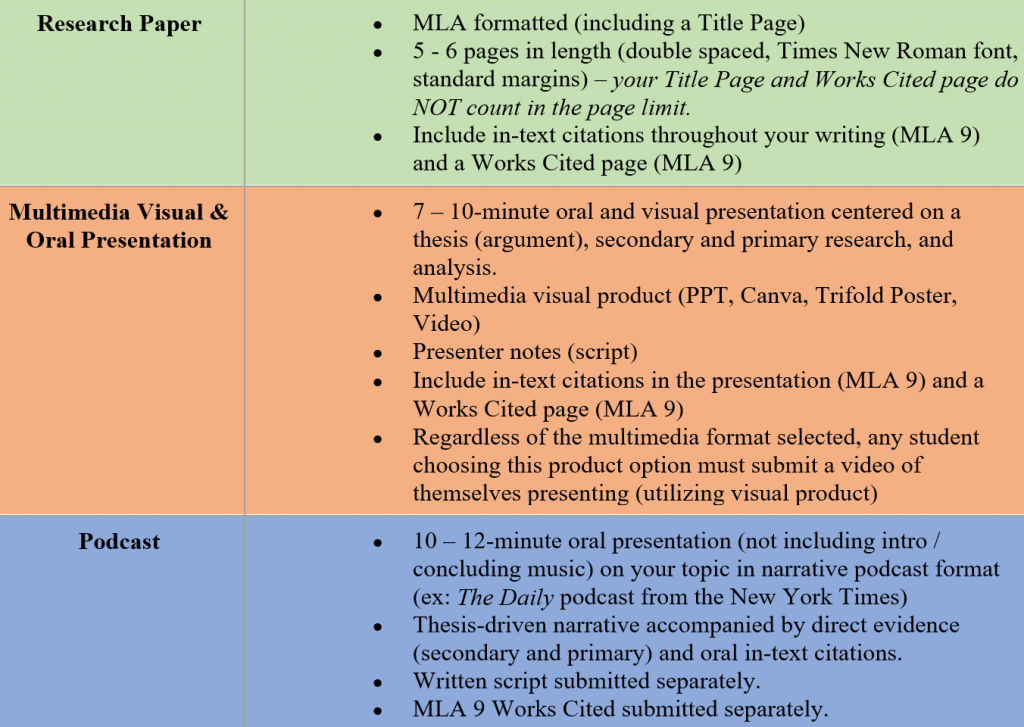

9th Grade History Research Project – Final Product Options:

Class Opener / Starter Examples:

Daily Agenda Examples:

Class & Group Activities:

Concluding Discussions & Exit Tickets:

An example of updating the topic / conversation to 2024: