Framing

The first professional development conference I ever attended as a teacher was the Beginning Teachers Institute (BTI) hosted by New York State’s Association of Independent Schools (NYSAIS). This was back in October of 2009 and I had only been teaching for a month. Heading into the conference I was exhausted and nervous about being judged for the rookie teacher that I was. Upon arrival, we were immediately placed into cohorts by academic discipline and asked to introduce ourselves and reflect on our first few weeks in the classroom. Thankfully, I was seated at the end of the circle, so I luckily was able to listen to other peoples’ reflections before I had to share. As my turn approached, I remember listening to the woman next to me talk about her experience teaching 9th grade world history for the first time. She mentioned the same adjectives and emotions that most people shared, but she added one comment that has stuck with me in my teaching career. She shared that the last time that she had learned the content that she was now responsible for teaching was back when she was a 9th grader in her high school world history course. She said that she was not the best student, especially when it came to ancient and classical history, and that her recollection of the material was sparse at best. With so much time between when she was a student of the material and when she had to teach it, she was finding herself spending an exorbitant amount of time each night researching and writing lesson plans. Her preps were taking her two to three hours a night, and she was barely staying a page ahead of her students. Her earnest desire to “know her stuff” and provide a classroom experience that was much more engaging and informed than the one she had 10+ years ago came through in her share-out. What really stuck with me, though, was how she described herself as a professional researcher rather than a teacher. So much of her job in those first few weeks of teaching was taking deep research dives into content, re-learning the material herself, and then crafting lesson plans that expanded the learning experience for her students. She concluded her reflection by stating — “I don’t know what it means to be a teacher yet because I am still an exhausted student.” I have no idea what I said in the group share-out after that comment, but I do remember deeply connecting with this woman’s assessment of early teaching. I barely had time to think about my own pedagogy or intentional curriculum design because there was so much to learn about my subject.

Looking back on this moment, I can almost feel the apprehension and overwhelming exhaustion that shaped my first few years of teaching. I now can recognize that I actually was developing some curriculum (intentionally and unintentionally) during those first few years, but I was so focused on the effort to learn all that I didn’t know (ha!) that I often forgot to acknowledge the teaching, discussions, and skill development that happened in the classroom with that newly acquired content.

I finally felt a shift around year 3 of teaching, when the material started to feel a bit more familiar and less daunting, which freed me up to think about teaching strategies and student experience more intentionally. This was also the year that I first participated in a formal curriculum redesign at Emma Willard. We were overhauling our antiquated 9/10 world history program, and the history department “retreated” to a local coffee shop for the day to workshop some big picture ideas for the redesign. I was the newest and least experienced member of the department, so I did a lot of listening that day. About half way through the session as the morning coffee was wearing off and we were starting to talk ourselves in a circle, a veteran colleague of mine (Carol Bendall), had a design breakthrough. She suggested that we throw out the yearlong survey approach and create semester-long regional electives with student choice (sound familiar?). The energy and collaboration that followed was exhilarating, and I walked away from that day feeling proud of the proposal that we had put together. It was as if a door had been unlocked in my teaching world and I was being invited into one of the most impactful and energizing aspects of teaching — designing curriculum that reflected my intellectual values and identity as a scholar. In all of my undergraduate and graduate work, I never took an education class. I never formally studied curriculum design and educational pedagogy, yet someone, somewhere, trusted me to contribute to the crafting of new courses. I loved the big-picture creative thinking, the messiness of sifting through competing ideas, and the process of picking up all the different parts and starting to put something coherent and organized back together. Much like my teaching style, I am sure that my approach to curriculum design in those first few years primarily served the students who learned like me. I had minimal awareness of student-led learning, backward design, and UDL frameworks at this point, so my contributions were often limited to what I would have wanted and needed out of a 9th grade history course when I was a student. I definitely felt very green in these conversations, but I also remember feeling energized and empowered in these collaborative design sessions.

Fast forward to year 15 of my teaching career, and collaborative curriculum design is such a large part of my teaching and discipline lead experience. I have benefitted immensely from working with colleagues who DO have an extensive background in educational theory and curriculum design. For example, conversations with Alicia Hale about blended learning have broadened my understanding of how to approach curriculum design and lesson planning from the student perspective. After reading The Shift to Student-Led (Tucker 2022) for faculty summer reading last year, I now try to incorporate choice, rotating stations, and in-process feedback more often in my 70-minute lessons. Additionally, working so closely with David Fierce and observing his humanistic (and Jesuit) approach to learning challenged me to think creatively, ask bigger philosophical questions, and incorporate student-led discussions as a primary mode of learning. David was great at just asking “why not?” or “so what?” in discussions, and his ability to stop kids in their thinking tracks and get them to wrestle with the material was amazing. David also taught me the value of teacher-student relationships in the learning experience. His care for his students was constant and boundless, and they entered his classroom excited to learn because they knew they were seen and cared for by their teacher. I can often get caught up in the pace of the day, the detail of my lesson plan, or the endless grading pile that I have to tackle, but when I see a “Fierceling” in the hall (one of David’s many student mentees), I am reminded that none of it matters unless I am connecting with and making time for kids, and that is a powerful reset for me.

Teaching at such a collaborative school has allowed me to continue to be a student of curriculum design while also providing me with ample opportunities to practice and hone my curriculum development skills. From my experience collaborating with humanities colleagues in our 9/10 redesign back in 2018 to the proposal process for the 9/10 revisions this year (2023), I have learned that EPS is a school where curriculum truly is dynamic and always evolving. I have also learned that the complex web that makes up curriculum is far more interconnected and interdependent than I ever realized in my first few years of teaching. While I don’t always see or understand the many “tugs” on a curricular decision, I now realize that integration is far beyond how I often define it in my own disciplinary silo, and it excites me to see that veil lifted and to think big about the ways in which a single class or program impacts a broader curricular ecosystem.

Because curriculum design is such a large part of my experience and identity as a teacher, I often find myself taking strong stances on curricular decisions, especially when it represents a fundamental aspect of my discipline or is a strongly held belief amongst my colleagues. I am proud that I stand up for the integrity of my academic field in curricular discussions and that I trust my colleagues and our collective experience in the classroom to guide our decisions and practices. AND…I can sometimes dig my heels in too deep and fail to see the ways in which other constraints complicate the path forward. I may not always agree with the importance of these institutional constraints, but I do believe that I am getting better at recognizing their existence and backing down from my “defender of history” mountaintop. The invitation to be a part of these curricular conversations as a discipline lead has made all the difference in helping me grow in my “big thinking” skills. If and when I am ever in a position to invite more teachers into the room to participate in curricular discussions, I hope that I will be the type of leader or mentor who willingly opens the door, makes space for new ideas, and helps others cultivate institutional thinking skills.

Curriculum | Discipline Design

| Indicator | Comments & Evidence |

| Designs and implements courses that reflect teacher mastery of their academic discipline and its teaching methodologies | History is such a fluid academic discipline. You would think that the past would stay the same, but teaching the past to a modern audience requires the curriculum to be dynamic, relevant, engaging, and constantly evolving. Every single school that I have worked at has been in the process of overhauling its 9/10 program when I joined the faculty. At first I thought that this was a coincidence and that I was just really lucky to be gaining all of this experience in program redesign in the first few years of my career. By the third or fourth school, I started to figure out that no one “loves” their 9/10 program and that curriculum is always a dynamic, shifting world, especially when looking at such a broad field as ancient, classical, medieval, and modern world history. I am a researcher by nature, and so much of my own learning process is relearning, revising, revamping, and updating lessons, assignments, and connections for students each year. On paper, I have taught the same course many years in a row, but in practice I don’t think that I have ever walked into a class and hit play on a prep from the year before. I have always seen myself as a historian with the ability to fake it as a social scientist. EPS has taught (and forced) me to be a flexible and versatile teacher. To tear down my disciplinary walls and embrace the scholarly exploration of political philosophy, environmental literature, library sciences, literature, art history, and so much more. Ironically, I was hired as a humanities teacher and was a fish out of water my first year at EPS while I stumbled through teaching Middle Eastern Literature, Media Literacy in the Digital Age, and Public Speaking. Courses Taught at EPS: US History, Medieval Euro., Modern Euro., Revolutions in Thought, Modern Middle Eastern Literature, Authority, Migration, Connections, Arches, Media Literacy in the Digital Age, Public Speaking, Civics Courses & Programs Designed (individually or collaboratively) at EPS: Humanities Redesign of 9/10 Program (2018 – 2019) US History, Authority, Migration, Connections, Media Literacy, Arches (with Elena), Medieval European History (revamped with Bess), Civics Humanities Seminar (interdisciplinary faculty seminar my first year at EPS) Independent Study Faculty Mentoring Current 9/10 Proposal & Redesign Process (2023 – 2024) |

| Designs and implements courses framed by the school’s pedagogical tenets – inquiry, experience, and integration | My experience with both the 9/10 redesigns at EPS (the first in 2018 – 2019, the second in 2023 – 2024) has challenged me to think differently about curriculum design. I’ve learned a lot about the complex relationship between school mission, school culture, curricular integration, interdisciplinary collaboration, disciplinary tenets, and individual teacher pedagogy. I’m trying to think beyond my disciplinary bubble and to see the institution (and the curriculum that embodies this institution) as an interconnected ecosystem that the Social Sciences discipline is just one part of (and then I am an even smaller piece within that part). What does integration really mean? What does it mean for a 9th grade social science course to be part of a bigger humanities program, a broader 9th grade experience, and a progressive 9 – 12 social science program? How can one trimester course serve all of these purposes in a program? What do humanities courses and curriculum “hold” and “house” for a school like EPS? Current events, civic education, civil discourse, EICL / identity work, global citizenship, core academic literacies such as critical reading and analytical writing, discussion-based learning, digital research and library / information sciences, academic integrity and authority, collaboration and relational learning, politics and ethics, processing major societal moments together… I’m trying to think big and beyond, which is a new type of thinking for me because so much of being a teacher is thinking small (your courses, your practice) and within a particular discipline. I honestly find it difficult to keep track of all of our “tenets” at EPS. We have the mission, the vision, the academic tenets (inquiry, experience, and integration), and then the connection and relevance components of our curricular values (as stated in ADIG this year). Trying to figure out how one course or program can reflect and serve all of these values while still remaining accessible, manageable, and developmentally appropriate for a new 9th grader (or a different student / grade level). |

| Collaboratively designs and evolves course curricula that are reflective of their academic discipline’s philosophy and derivative of the school’s overarching philosophy | I’ve been thinking a lot about collaboration this year. In some ways, EPS is the most collaborative school that I have taught at. Most of my courses are taught with at least one other colleague, and for the first 5 years of my time at EPS, I was often the “newbie” to the team, so I did a lot of listening to those who had taught courses before and implementing curriculum that was already established (but still open and flexible enough for me to impact in certain areas). Over the past few years, largely since David’s departure and Bess’ shifting role, I have started to step into the role of “been here the longest and knows the curriculum the most” on collaborative teams. Example of collaborative curriculum design in my time at EPS: 9/10 humanities redesign (2018 – 2019) — paired with Verity in the fall trimester to create the overall structure of the 9/10 program (within certain guiding parameters). I tend to be the logistics and planning person on collaborative teams, especially when it comes to curriculum design and creation. I definitely contribute ideas, but I would not identify as the big-picture, out-of-the box, creative dreamer of a team. I’m good at hearing an idea and putting it into action. I help bring people down from 30,000 feet to 5,000 feet and get the ball rolling with realistic next steps. I take detailed notes (because that is how I learn and remember), I organize and make lists, I try to delegate, and I synthesize / sift through the details to pull out a cohesive vision / lesson plan. My areas of growth in collaboration & curricular design — trusting and making space for my colleagues to have ownership over the final product, delegating and stepping back, being open to alternative approaches to a course or topic, asking follow-up questions in a supportive way, not taking on too much myself, and being patient with others. Institutional challenges to collaboration — needing the time and physical space to design curriculum and team teach, the sheer number of “cooks” in the kitchen, having a collegial culture where no one has explicit ownership over a team or a course so there are some blurred lines in terms of responsibility and colleague-to-colleague dynamics, (in the humanities specifically) needing to work with multiple disciplines to plan and teach a single course, the lack of consistency (in terms of students, staffing, and collaborative teaching teams) throughout the year, the varying work styles and schedules of colleagues, not being in the same office with those I teach with so natural and daily moments of collaboration and planning are fewer. |

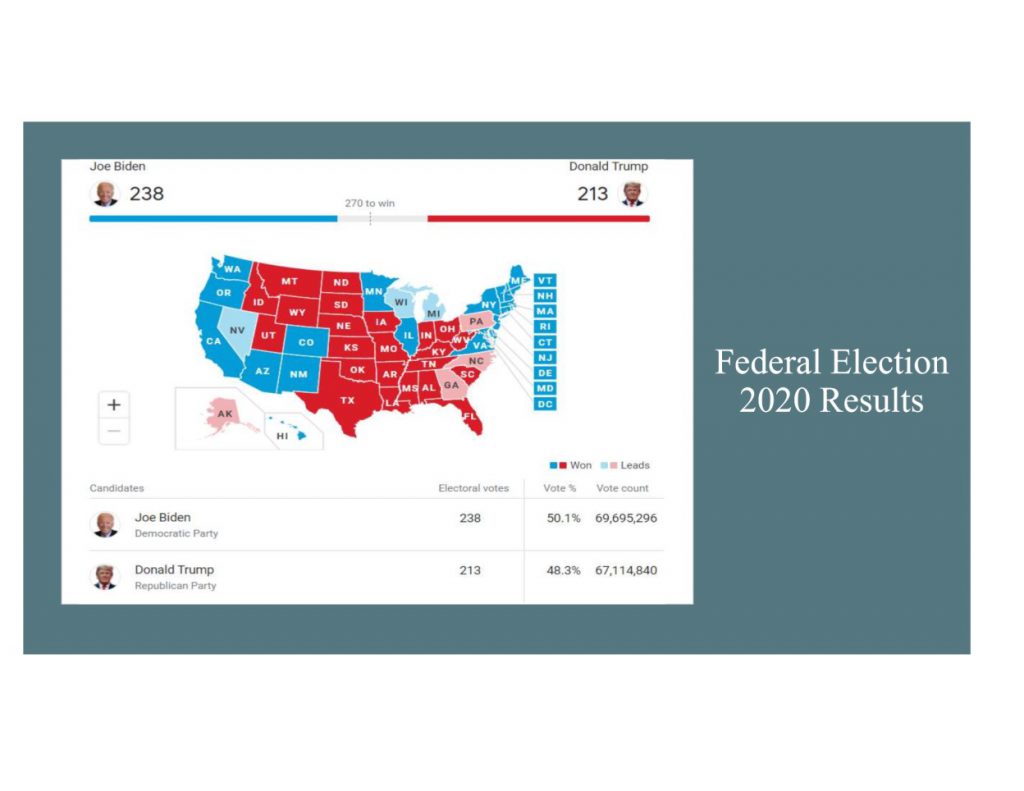

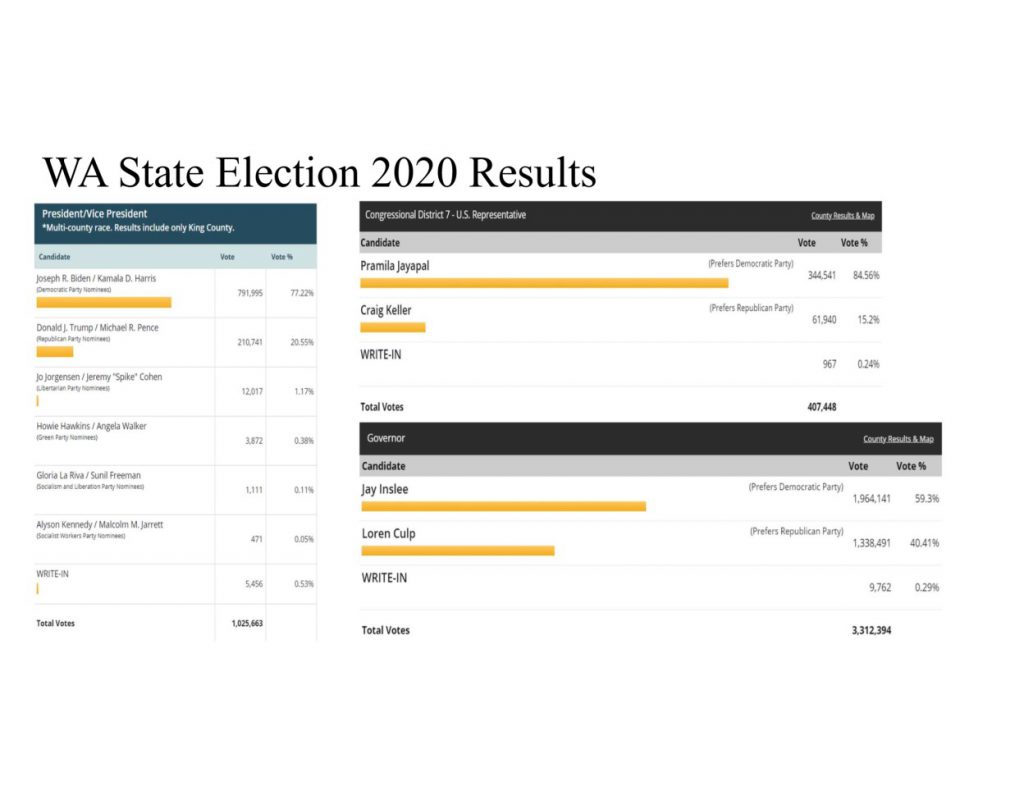

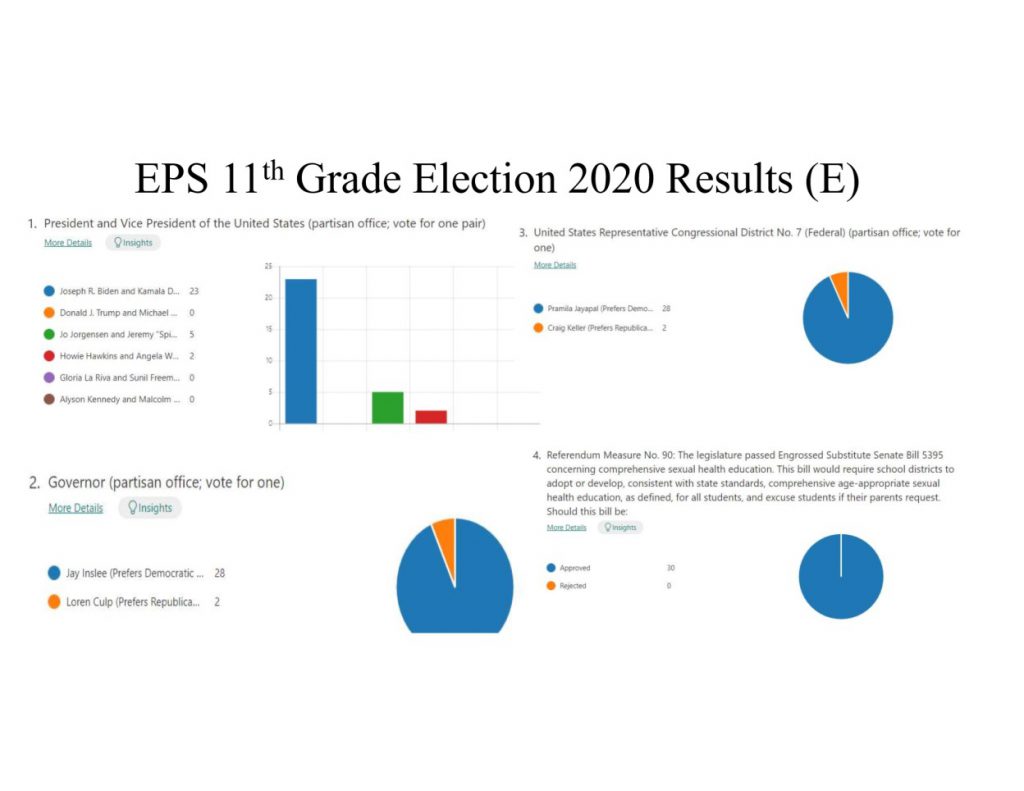

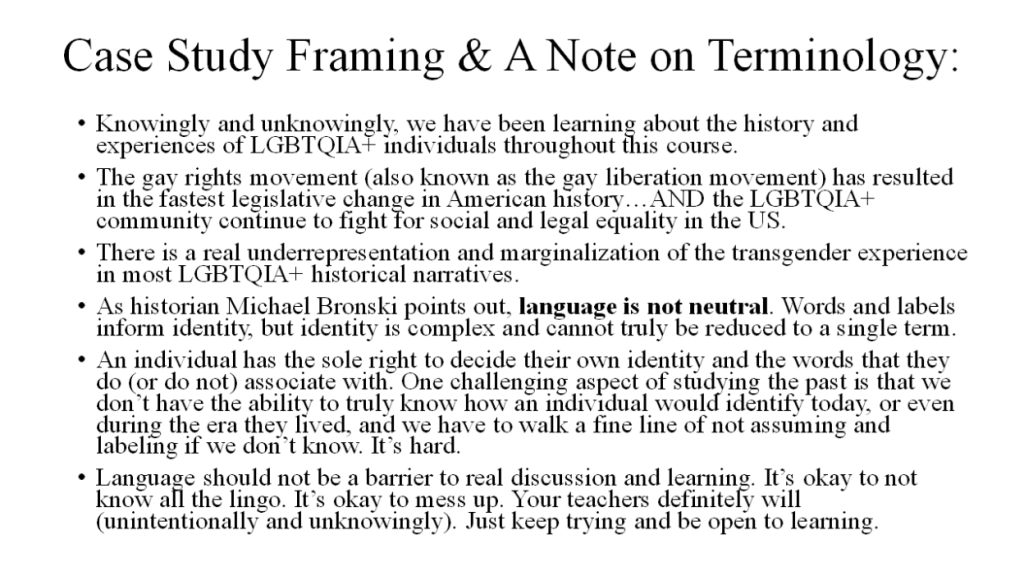

| Updates course content to reflect the contemporary world | In my limited experience, it means something completely different to teach history, particularly US History, post-2016. Current events feel all-encompassing, social media makes news (and fake news) instantaneously accessible, and social justice has taken on a whole new meaning and momentum in high school curriculum. Every lesson connects to social movements or moments outside the classroom, and every teenager is trying to navigate this messy and divisive world (especially during a pandemic). I teach far less historical content than I did 5 or 10 years ago, but I teach far more about the world right now, and that feels both exhilarating and absolutely daunting and exhausting. Sometimes I feel so burnt out from talking about partisan politics, the next onslaught of human rights violations, the always-changing geopolitical tensions, the next scary threat to national security, or the ways in which society continues to fail this generation that I feel like a cranky elder millennial and rush home to read anything BUT scholarly writing or listen to the news. I constantly have current events fatigue and feel an emotional load to what I teach now in a way that I never felt when I simply taught the Han Dynasty. All of this is to say, most of my curriculum is connecting with the contemporary world and fostering and facilitating civil discourse in the classroom. A lot of my curricular design work has also been focused on updating courses to be more representative of the student identities in our community. This includes creating the first LGBTQIA+ history unit in US History, advocating for the addition of a South Asian history course, mentoring numerous independent studies focused on gender history (since this is an area that we do not have a dedicated academic course in our curriculum), and helping to craft discipline-specific EICL “audits” (self-studies) and EICL language for our discipline syllabi. |

Professional Development

While the “Program and Professional Development” indicator is not technically a part of the Senior Teacher PDP, I wanted to take a moment to reflect on the role and impact that professional development experiences have had on my teaching career thus far. The first three independent schools that I taught at were on the East coast and had deep endowments for faculty professional development. It was both an expectation and part of the scholarly culture for faculty and staff to seek out learning experiences that expanded their professional community and knowledge of their field. These opportunities have been some of the most rewarding and reenergizing parts of my teaching. They allow me to keep being a student, they help me see beyond my own classroom and school, they connect with fellow educators with a diversity of experiences and backgrounds, and they challenge me to always be rethinking and updating my teaching practices. While professional development is always discussed at EPS and baked into our internal culture (ex: PD days, Evo of Instruction, EICL learning groups, affinity spaces, etc.), the active pursuit of and funding for learning experiences beyond EPS feels harder to access. Whenever I take the time to research and apply for professional development programs outside of EPS, I am always reminded that professional development is a critical part of teaching that feeds my soul. I need to continue to prioritize and seek out these experiences, because they help me be a better teacher, scholar, and colleague.

Below are some of the professional development experiences that I have been fortunate enough to be a part of:

- National Endowment for the Humanities Landmark Workshop, “The Rochester Reform Trail,” Rochester, NY

- Gilder Lehrman Teaching Seminar, “American Women from the Colonial to the Modern Era,” NYU

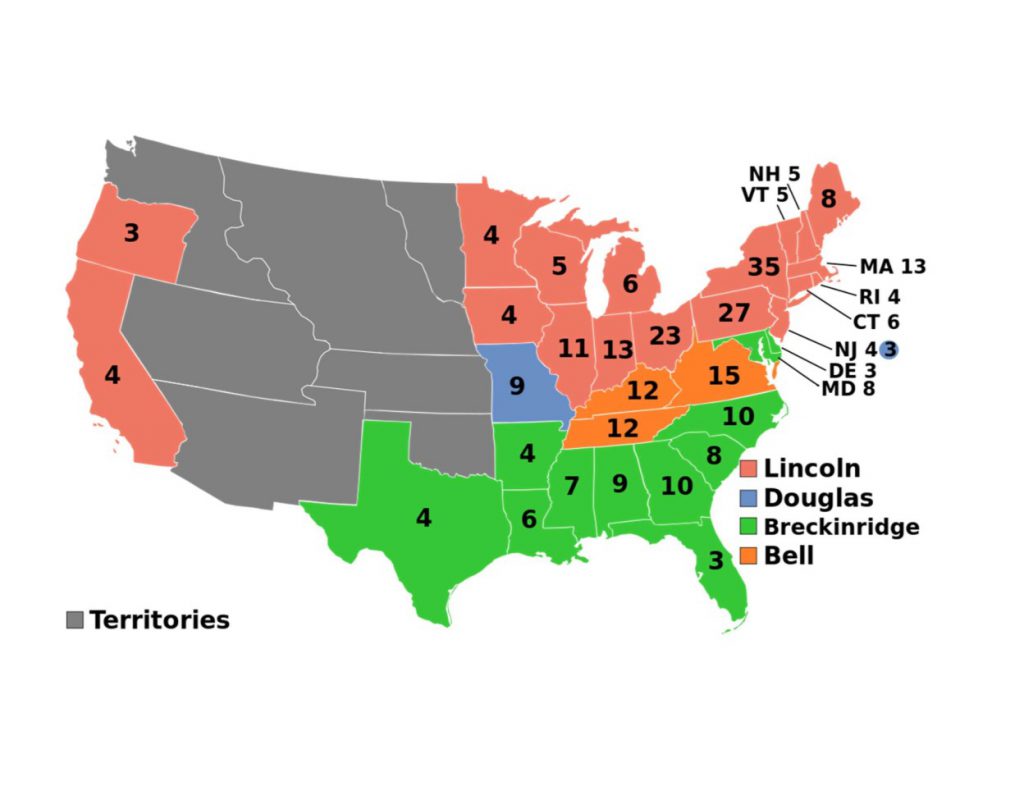

- Gilder Lehrman Teaching Seminar, “The Age of Lincoln,” Oxford University

- AP Summer Workshop, U.S. History, The Taft Educational Center, Watertown, Connecticut

- Facing History and Ourselves Seminar, “Teaching the Reconstruction Era,” Boston, MA

- New York State Association of Independent Schools, Beginning Teaching Institute

- Stanley H. King Counseling Institute, Fountain Valley School, Colorado Springs, CO

- National Association for College Admission Counseling (NACAC), member

- Blackberry River Retreat for College Counseling, Mt. Holyoke College

- New York State Association for College Admission Counseling, Summer Institute, Skidmore College

- NWAIS Emerging Leaders Institute

- At-Large Board Member, the Attic Learning Community, Woodinville, WA

- NWAIS Building Better Boards Series

Examples of Curricular Design

Unit Design:

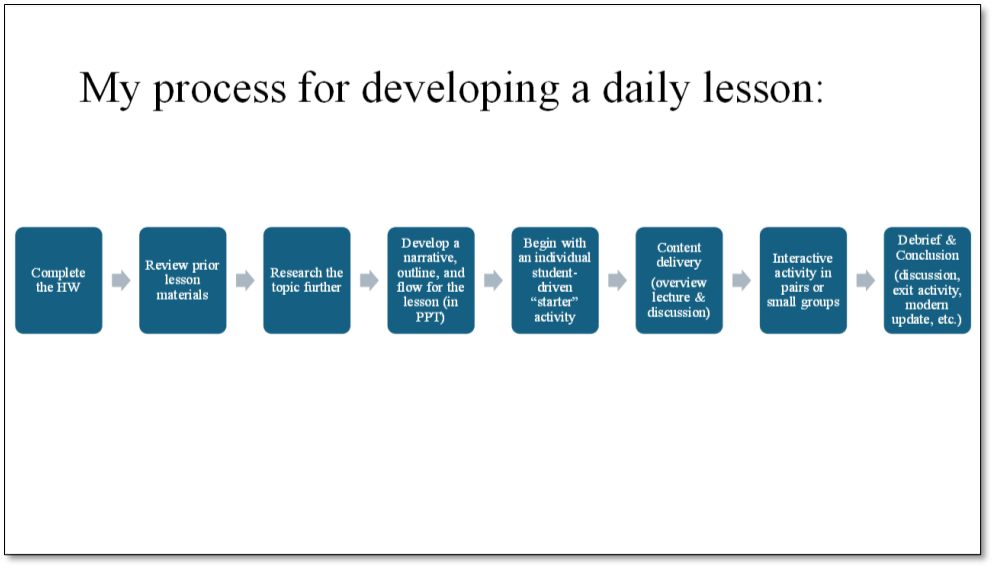

Lesson design: